"I Haven't an Inner Life"

Granta's Re-Issues the Exquisitely Boring Diaries of Virginia Woolf: 1915-19

For most of us, the sweeping arc of history is a backdrop against which we act out our day-to-day lives. What diarists choose to include and omit is fascinating. The best of them captures the poetry of days becoming weeks, months, and, inevitably, years. Routines are established, relationships formed and broken, and order is slowly brought to the chaos of random events. Defoe’s fictional Journal of a Plague Year moves according to a weirdly beautiful rhythm created by the Parishes’ reports of the dead. Georges Perec’s observations from a café table in Saint Sulpic Square are broken by a refrain of bus schedules. Time lapses according to a garden’s seasons in May Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude. And in the diaries Virginia Woolf kept from 1915 to 1919, wild mushroom forages, air raids on moonlit nights, train trips to London, and many, many visits with friends mark the days.

News of the battle rather better today. L. heard guns yesterday morning. Afternoon in the garden. L. planted vegetable. I sewed. L. found ground ivy yesterday. We forgot the change to summer time on Sunday, so didn’t have breakfast till 10. I heard what I though was the first half of cuckoo, but the book says its too early. More clouds yesterday, but still sunny & windless. 12 aeroplanes in order went over us after tea. Tortoiseshell butterflies out. We went to Lewes.

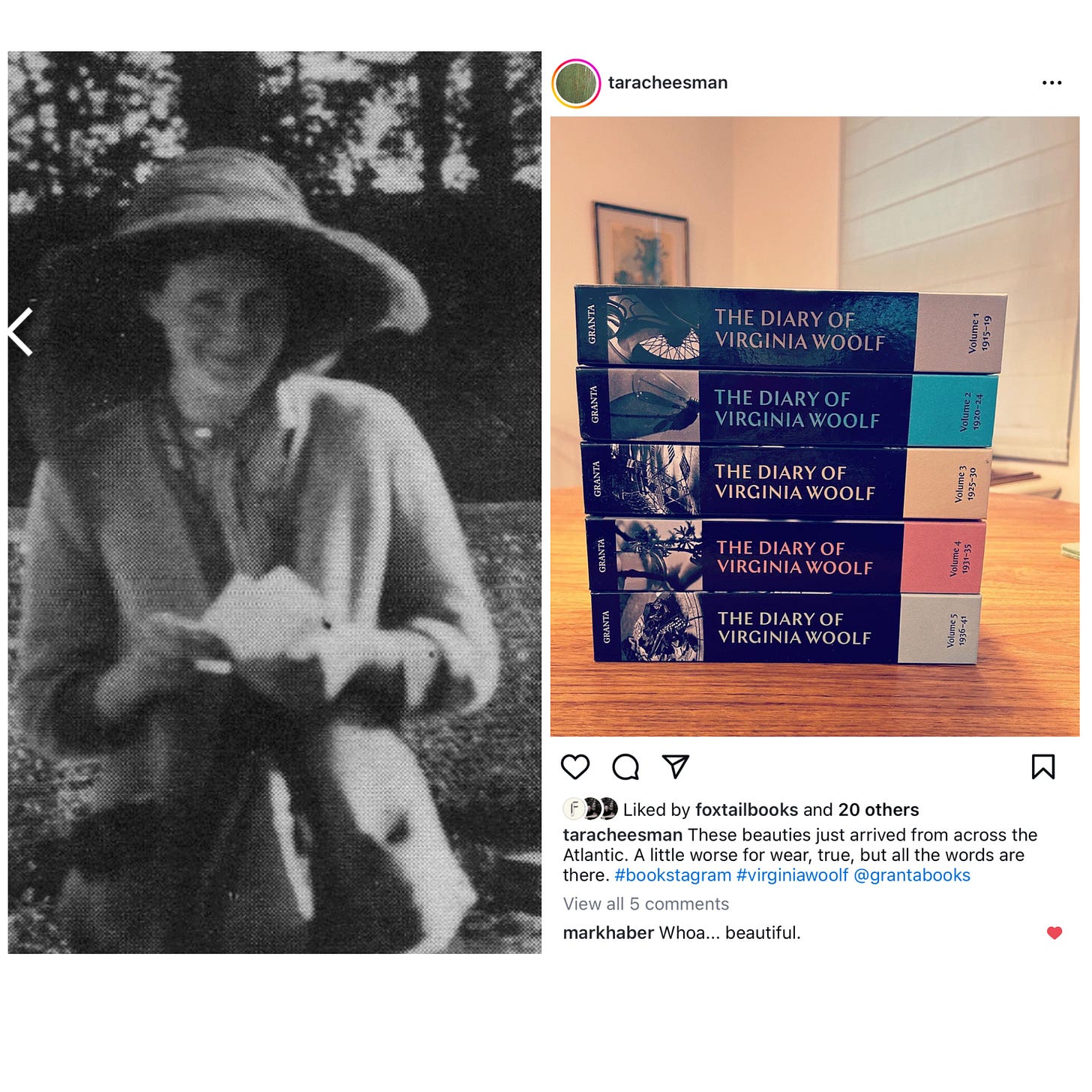

Granta recently reissued all the diaries of Virginia Woolf in a handsome five-volume set, re-instating parts left out of the previous edition, such as the diary Woolf kept between 1917 & 1918 while living at Asheham House in Sussex (which I quote above). I’m halfway through Volume 1, written during WWI, an event that forced most of the Bloomsbury group to quit London for the countryside. The events we now know to have been critical globally and historically are barely mentioned. Instead, as I suppose is often the case with diarists, Woolf confined her observations within the microcosm of her world. She writes about friends and acquaintances, mending tire punctures, and the weather. Her remarks about the war are oddly fleeting – seeing German POWs working in the fields, the sounds of planes flying overhead, and guns in the distance. On clear nights, Virginia writes of gathering in the kitchen with Leonard and the servants, waiting for the bombing raids to end. Rationing is a bother. There are rumors that peace talks are happening, and the fighting will end soon. She and Leonard make regular trips to and from London. They write articles and reviews. Leonard continued his government work, gave talks to the Women’s Guild, and in 1917, they started their publishing house. Crowds of people pass through these pages. Some of the names I recognize but most, despite many helpful footnotes, I do not. Bloomsbury was an ever-expanding and contracting circle of friends and acquaintances.

Bloomsbury’s shadow, to me, appears to be much too large for those casting it. Many of the members are problematic when separated from the collective herd, and I liken their cultural impact to today’s social media influencers, -- outsized in light of their artistic contributions. I’ve read that Leonard Woolf was responsible for the idea of “Bloomsbury” as a cultural force. But, as early as 1918, the thirty-six-year-old Virginia acknowledges not only the existence of a mythology the core members had cultivated amongst themselves but observes how it has become a source of fascination (and emulation) for a younger generation. She recalls Clive coming to tea on a Monday. “We talked chiefly about the hypnotism exerted by Bloomsbury over the younger generation...”

‘…In fact the dominion that “Bloomsbury” exercises over the sane & the insane alike seem to be sufficient to turn the brains of the most robust. Happily, I’m “Bloomsbury” myself, & thus immune; but I’m not altogether ignorant of what they mean. & its a hypnotism very difficult to shake off, because there’s some foundation for it. Oddly, though, Maynard seems to be the chief fount of the magic spirit.’

No one can seriously argue Virginia Woolf’s brilliance as a writer (though some try). But what legacy have most of the other members left us? Who still reads Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians? Or marvel at the paintings of Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, or Dora Carrington over those of their contemporaries, which included Picasso and Frieda Kahlo? Bloomsbury was an endless self-promotion machine at its height – writing, reviewing, and admiring each other’s work. They are best remembered for their lifestyles and their strong affection for one another. Yet, the soap opera quality the relationships took on in their various incarnations - families, friendships, marriages, unconventional living arrangements, and inevitable betrayals – make today’s reality television shows seem puritanical. Quentin Bell’s excellent biography of his aunt, titled simply Virginia Woolf: A Biography, addresses (and often minimizes) these inherent dramas. But his sister, Angelica Garnett’s memoir, Deceived With Kindness: A Bloomsbury Childhood, leans into the less savory aspects of those relationships. Until she was eighteen, Angelica believed her mother’s husband, Clive Bell, was her father. In truth, her father was Duncan Grant, her mother’s bi-sexual lover. That same year Angelica married David Garnett, who was twenty-six years her senior, had been present at her birth, and was her biological father’s former lover. This is only one of the many overlapping circles in the awkward vin diagram we call Bloomsbury.

Virginia Woolf herself was not a particularly generous or nice person, particularly when describing her friends’ foibles. She could frequently be mean, petty, and, apparently, not always accurate in her recountings. Quentin Bell’s introduction to Volume One quotes his father, Clive Bell’s memory of Leonard reading aloud from the diaries to a group of his and Virginia’s friends after her suicide.

‘Leonard Woolf…stopped suddenly. ‘I suspect,’ said I, ‘you’ve come on a passage where she makes a bit too free with the frailties and absurdities of someone here present.’ ‘Yes’, he said, ‘but that’s not why I broke off. I shall skip the next few pages because there’s not a word of truth in them.’

Virginia’s notes regarding the servants, who were devoted to her and Vanessa by all reports, are particularly awful. Alison Light’s Mrs. Woolf and the Servants: An Intimate History of Domestic Life in Bloomsbury shines a much-needed beam of (!) light on these women who Virginia and Vanessa, free-thinkers and professed feminists though they were, considered beneath them. Mrs. Woolf and the Servants makes the point that while the sisters were progressive for their time in many ways, they were still women “of their time.” Unlike their servants, they did not need to work to live comfortably.

It’s surprising how little work for pay people who keep diaries seem to do based on what they record. By the end of 1919, Virginia had been married for six years and had published her first two novels, The Voyage Out and Night & Day. She mentions the occasional book review or paper she or Leonard are working on, her husband’s various government and private work (the more I learn about Leonard Woolf, the more I suspect he was the best of Bloomsbury), and the beginnings of the Hogarth Press. But it’s hard to see how such a piecemeal income -- the gig economy apparently existed long before it was given that name -- was enough to pay for a lifestyle supported by servants. Until you realize Woolf received an inheritance from an aunt, approximately five hundred pounds per year (or $3,600.00 per month in today’s dollars), and shared the servants with her sister Vanessa, who lived nearby. Most of Bloomsbury had similar financial situations, allowing them to live primarily idle lifestyles and create art free from worries about how to pay the bills. E.M. Forester, who seems somehow to have managed to avoid the incestuous entanglements of Bloomsbury despite being close to all the various parties* and considered a founding member himself, wrote, “In came the nice fat dividends, up rose the lofty thoughts, and we did not realize that all the time we were exploiting the poor of our country and the backward races abroad, and getting bigger profits from our investments than we should.”**

Despite the numerous dramas continuously unfolding between and among the group’s members, Virginia’s journals reveal how vast swathes of life –the majority– are devoted to the mundane (though never trivial) maintenance of our persons, dwellings, and comfort. And it is in those observations that I took pleasure and comfort. Most histories, like novels, are edited. The paragraphs are pared down until all that remains are the exciting bits. Virginia’s diaries reveal how little space those bits occupy for most of us. She was a diligent cataloger of events but not ideas. She neglects to mention that she’d attempted suicide in 1912 and had only recently recovered from a breakdown that lasted until 1915, the year the diaries start. (Though she mentions the nurse who cared for her without providing context). And it seems never to have occurred to her to do so. The closest we get to self-examination is when she writes: ‘Ottoline keeps one [a diary] by the way, devoted however to her “inner life,” which made me reflect that I haven’t an inner life.’ A footnote gives Lady Ottoline Morrell’s recollection of the same conversation. “When we were talking about keeping a journal, I said mine was filled with thoughts and struggles of my inner life. She opened her eyes wide in astonishment.”

* I’m embarrassed to admit I didn’t know the Schlegel sisters of Howard’s End were based partly on the unwed Virginia & Vanessa Stephen.

**Forster was also of his time, as this quote unfortunately demonstrates. As for his claim they“did not realize”, Forster is being disingenuous. Virginia, at least, took part in (and recorded in her diary) conversations with Communist-leaning friends on the subject of giving up “capital”.

Books I mention (and some I don’t):

The Diary of Virginia Woolf, Volume 1: 1915-1919, with a foreword by Virginia Nicholson, Introduction by Quentin Bell, and edited by Anne Olivier Bell. London: Granta Books, 2023. 465 pages.

A Journal of a Plague Year by Daniel Defoe. New York: Penguin Group, 2003. 336 pages.

An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris by Georges Perec, translated by Marc Lowenthal. Cambridge: Wakefield Press, 2010. 72 pages.

Journal of a Solitude by May Sarton. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992. 208 pages.

Virginia Woolf: A Biography by Quentin Bell. London: Random House UK, 1990. 560 pages.

Eminent Victorians (Revised) by Lytton Strachey, with an Introduction by Michael Holroyd. New York: Penguin Group, 1990. 208 pages.

Lytton Strachey: The New Biography by Michael Holroyd, the 1995 updated edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005. 600 pages. (I’ve included the biography, which I haven’t read, in the off chance I’ve done Mr. Strachey a disservice).

Deceived With Kindness: A Bloomsbury Childhood by Angelica Garnett. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1985. 181 pages.

Mrs. Woolf and the Servants: An Intimate History of Domestic Life in Bloomsbury by Alison Light. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009. 400 pages.

The Voyage Out by Virginia Woolf.

Night & Day by Virginia Woolf.

Howard’s End by E.M. Forster.