It's not entirely surprising that the American Mary Cassatt, who was childless and died in 1926, portrayed a gentler, less emotional, and more idealized version of motherhood in her work. Or that her paintings and drawings are frequently called "pretty." This is motherhood as experienced by the affluent class -- the privilege of parenting with servants. In a way, she was as much a social realist as Kollwitz. But Cassatt’s messaging is more subtle, moving women expected to remain in the background to the foreground of her work. I didn't realize how many paired women and children in her paintings and drawings aren't mothers with their offspring but portraits of children with nannies and wetnurses. Once you know this, you can't unsee certain details, like the differences in dress. For example, the bright orange robe worn by the mother in the oil painting Mother and Sara Admiring Baby, the transparency of the woman's sleeves in Maternity, or the elaborate lace panels of the dress in Mother Nursing Her Baby all scream wealth. The servants’ clothes are much more somber. The women’s faces also tell a story. See where they direct their gazes: society women tend to stare directly at the viewer, often with bright eyes and happy smiles. The nannies look to their charges.

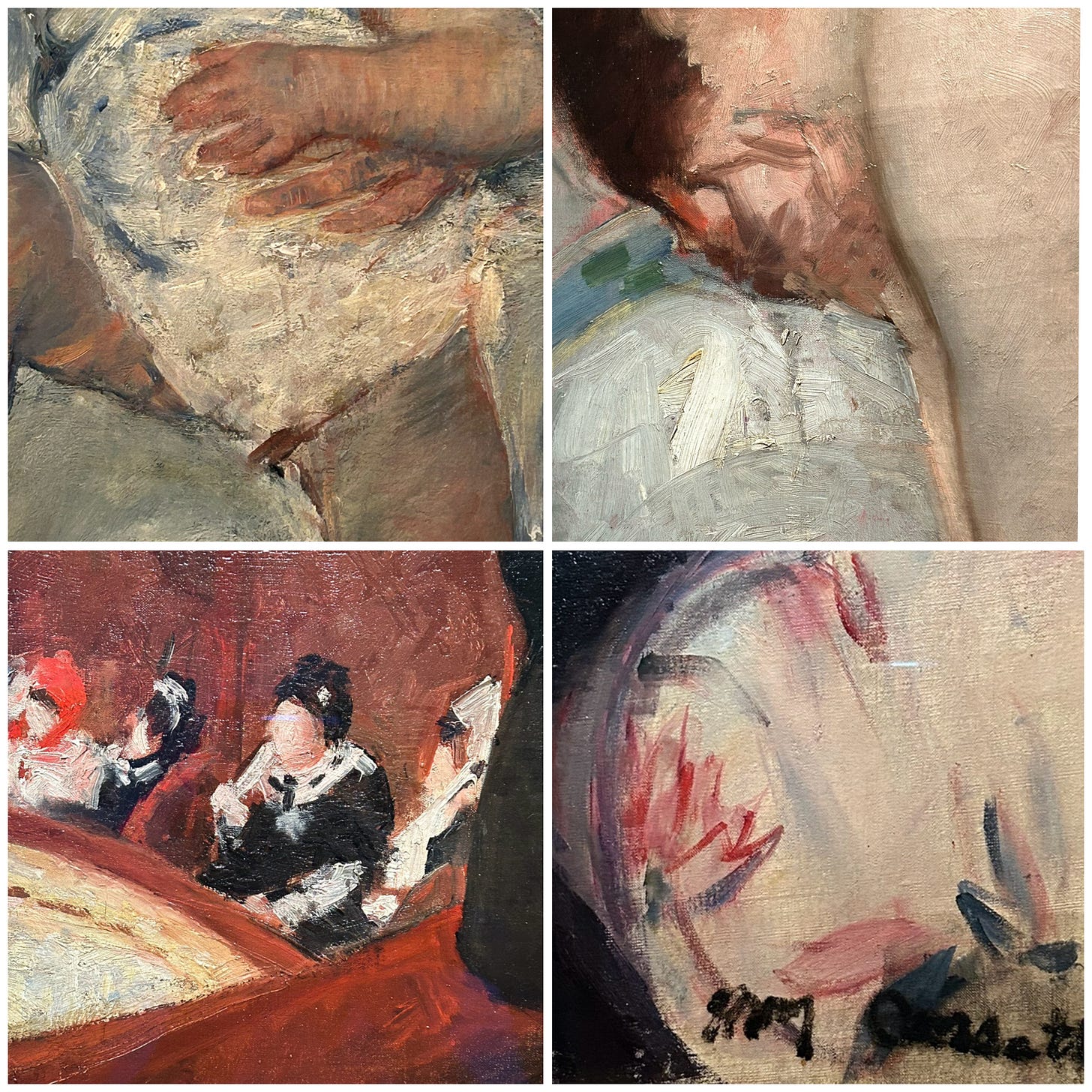

Cassatt worked in soft colors and scratchy lines in her etchings. But her oils and pastels are filled with bold brushstrokes and rich pigments –she mostly avoids the chalky palette that plagued so many of her male contemporaries. A slash of brown sepia represents a fold of baby flesh. A fierce flurry of thick paint describes the water in a basin and the hand suspended over it, scooping it to the model's face. A pattern of flowers loosely sketched on upholstery becomes an abstract painting when cropped. Theatergoers in the background of a portrait, represented by loose daubs of paint, are more interesting than the tightly painted woman who is the actual subject of the painting.

An earnest young woman walking ahead of me at the Mary Cassatt at Work exhibit in Philadelphia explains to her companion how Cassatt was different from her contemporaries because her work subverted the male gaze – and in a way, that's how this entire exhibition is framed. The women whose portraits Cassatt painted are not positioned as objects to admire but as our companions in the theater box. Their bodies are natural and relaxed, as if they just looked over at the viewer during intermission, ready to discuss the play so far. I see it. The intimacy between friends and equals versus artist and model. However, according to her letters, Cassatt was something of a taskmaster, asking her models to hold long and uncomfortable poses. Which might explain the feeling of separation, of distance, of a figure frozen -- despite our being invited into the composition.

Cassatt, the artist, as a feminist icon, doesn't entirely work for me. Despite knowing she was a fierce proponent of women's rights, the work itself always teases at something in the back of my brain. Degas could have done the bravura background of the pastel painting Woman in a Black Hat & a Raspberry Pelisse. Or Van Gogh? Gauguin? Cezanne? Manet or Monet? She shared a dealer, Ambroise Vollard, with them all. She was the only American invited to join the French Impressionists and one of just three women. When she stopped painting late in life, she worked towards placing her friends and contemporaries' works (mostly male) into the hands of American collectors. There are shades of Sargent in a portrait of her niece, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair. Reproductions can't do it justice. The oil painting is approximately 3' x 4' but appears larger in person. The bright blues of the chairs and the tartan of the dress sash and socks, the slouching child, combined with the dramatic diagonal of the composition into the back corner of the room, is gorgeous. The original's richness and sense of depth don't transfer to the page. Yet even here, we are told there is some outside influence. Rumor has it that Degas suggested how the corner is drawn in the room's background. Why do we care? Why did this small piece of information survive the passage of time? The woman absorbed influences like a sponge.

Cassatt's most successful and ambitious work is arguably her series of ten drypoint etchings, based on the Japanese woodblock prints floating around Paris in the nineteen-oughts, which Degas and other artists enthusiastically collected. Even in these, she had help – a master printer named Modeste Leroy, who assisted her in “pulling the prints” and whose name she inscribed beside her own on the finished edition. Cassatt's paintings and pastels are easy to accept and/or dismiss. But the prints are something else entirely. A short video looped on an iPad-sized screen mounted to a gallery wall shows how Cassatt adapted the laborious process of Japanese woodblock printing to metal plates and a restricted palette. I couldn't find it online, but the monograph published in conjunction with the show summarizes her technique as follows:

"Cassatt conceived and designed the subjects, sketching the compositions first in graphite drawings and then rendering them in drypoint. Leroy, who covered the copperplates in fine aquatint grain, handled the involved choreography of aligning the multiple plates required for numerous and overlapping colors in a single composition."

As I said, the result is soft colors and delicate, scratchy lines. The Japanese Ukiyo-e artists (artists of "the floating world") created the Edo period's version of pin-ups, depicting famous geisha and other denizens of Japan's entertainment district in woodblock prints. These were made using multiple hand-carved blocks, including a key block of the drawing and separate blocks for each color. Several artists were involved in making one print, and for the more elaborate color prints, employing 10 to 20 blocks was not uncommon. Cassatt modernized and simplified the technique to suit drypoint on metal plates. It's not just the printing process that reminds us of the Ukiyo-e, but the way Cassatt composed her figures within their environments, like the Edo geisha. The work is academically and technically interesting, adhering closely to the Eastern inspiration while keeping the subject matter recognizably Western. It is unlike the work of her contemporaries and is, in fact, revolutionary.

So, for my feminist friend in the gallery, how Mary Cassatt depicts the women in her work is important. Even more radical is that she supported herself through the sales of that work. (Her family in Philadelphia made that a stipulation when Cassatt first expressed a desire to study art). She was able to purchase a printing press so she could work from home and, eventually, a small estate in France. She worked in pastels, oil paints, and printmaking. There's a discipline to her output. She was intellectually curious about her materials and methods. She was also generous and inclusive – crediting her printer as an equal collaborator when that was not done. Like Kollwitz, Cassatt's work displays a singular vision and sense of purpose.

I don’t always find Cassatt's subjects, separate from process, interesting. They stare out of the canvas with blank expressions like pampered Persian cats. They are too familiar and too pretty. I prefer the journey of her wrestling with composition, color palette, and technique to the final results of the struggle. Whereas Kollwitz's work is the image we see, stylized and saturated with raw emotion, which exists outside of any contextual scaffold we try to build around it. It is unexpectedly timeless. Though roughly drawn in her later works, Kollwitz’s subjects intimidate and move us. The care she took in posing and contorting the bodies (it's not surprising she took up sculpture) differs from the male German expressionists with whom she is sometimes lumped. Whereas they frequently relied on color to convey emotion, she remained loyal to working in black & white in her drawings and printmaking. Her early preliminary sketches for historical works like The Weavers Revolt read as illustrations of the events created using fairly traditional pen & ink techniques. Her style evolved in later works, becoming more Brutalist over time.

What makes these exhibitions exceptional (and worthy of attention) is their focus on these two very different women artists, their individual processes, and their dedication to their craft. Through the work, we experience Cassatt and Kollwitz grinding out the details of a painting, print, or sculpture—working and reworking the images until they are satisfied with their results.

There's another exhibit currently showing in New York that I haven't seen yet. In the Neue Galerie, a small private museum on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 86th Street works by the German artist Paula Modersohn-Becker are on view through September 9th. She, too, painted women and children, but in a very different way than either Kollwitz or Cassatt. She is another woman artist dedicated to her craft. There are more of them out there than history would have us suppose.

Exhibitions:

Kӓthe Kollwitz: A Retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art, NYC, through July 20, 2024.

Mary Cassatt at Work at The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, through September 9, 2024.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Ich Bin Ich /I Am Me at The Neue Galerie, New York, through September 9, 2024.

Books I mention (& some I don't) in no particular order:

Blood Brothers by Ernst Haffner, translated by Michael Hofmann. New York: Other Press, 2015. 192 pages.

February 1933, The Winter of Literature by Uwe Wittstock, translated by Daniel Bowles. Cambridge: Polity, 2023. 278 pages.

Color Woodblock Printmaking: The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e by Margaret M. Kanada. Tokyo: Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1995. 84 pages.

Kӓthe Kollwitz by Starr Figura, with Maggie Hire. New York: ARTBOOK D.A.P., 2024. 248 pages.

Mary Cassatt at Work by Jennifer A. Thompson & Laurel Garber. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024. 303 pages.

Recollections of a Picture Dealer by Ambroise Vollard, translated by Violet M. MacDonald. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2022. 384 pages.

Being Here is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker by Marie Darrieusseqc, translated by Penny Hueston. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2017. 160 pages.

Wonderful post, Tara. I love this work that you are doing!